Reflections on StreetLaw Brighton by Apostolos Pelekanos, final year law student, Sussex Law School (LLB Year Abroad).

As part of the final stages of the StreetLaw Brighton project, the students worked hard on their research, working in groups, presenting their experiences to faculty, and finishing off with written reflections on the past few months of StreetLaw Brighton. The below are some thoughtful and insightful reflections from Apostolos, a member of the StreetLaw crew.

Introduction

Being able to retrieve my thoughts on the StreetLaw Brighton project from the day I applied to it, I must confess that it turned out to be something completely different from what I anticipated. Even the title serves no justice to Street Law Brighton as throughout the academic year it managed to gradually expand on so many different levels and touch upon aspects that go far beyond the rather narrow “legal approach on the street art and graffiti in Brighton” concept that was implied.

Group C: Brighton Street Art and Graffiti Scenes

As pointed out in the presentation, Brent and I had to engage with a topic that required a “journalistic” approach, one that would demand the same level of research with the other Groups, but based on different sources (more practical and less academic). Given the fact that we had limited time to provide an adequate result of our research and the reasonable reluctance of the real actors of the Brighton scene to come and talk with some “law students doing some research”, we used Sinna One of Art Schism as our gateway to the local scene. And I believe it was the right thing to do, as in our one-hour private discussion and the ones we had collectively throughout the project we acquired such a level of information, that it would be impossible to even touch otherwise. Moreover, Sinna One is a smart and well-educated person, with deep knowledge and consolidated view on street art and graffiti, open-minded and always eager to answer any query.

In terms of approaching the issue of “Brighton Street Art and Graffiti Scenes”, we thought it would have been a good idea to firstly present some local festivals, namely the last year’s Urban ArtFest, the annual B.Fest and the Graffiti Jam 2007. That would have had a twofold function: it would demonstrate that Brighton still has a vibrant scene which attracts artists from all around the UK (Urban ArtFest) and promotes the work of talented local youngsters (B.Fest) and at the same time it would provide a historical background as to when the culture of graffiti and street art started creating an impact to the city and what was the initial feedback from local authorities such as the Police and the Brighton & Hove Council (Graf Jam 2007). An overall presentation of the positive impact of the local scene in the city was also necessary, no matter how obvious that would be. Thereinafter, elaborating on the impact with the aid of photographs taken by Brent himself, and not just picked off the internet, was thought to be necessary, so that the academics will have a visual idea of what we were contented. Lastly, a quick reference to the eminent local artists helped us to cover our subject matter in a more holistic way.

Before taking part in this project, I considered myself to have a liberal and quite tolerant approach to graffiti and street art, yet as we engaged more and more through the sessions, I found myself discovering some other positive aspects of graffiti and street art, namely the touristic one and how the city council itself embraces and actively promotes the local scene and of course the therapeutic one which we were lucky enough to witness firsthand in BYC.

Sinna One’s Questions

In my opinion, the idea of having a session with Sinna One asking questions to the group in relation to his practice was really spot-on because, right from the beginning, the real character and aims of the project have been revealed: to raise some level of awareness of this contentious issue and at the same to create/ grow/ reveal some necessary skills that any aspiring solicitor should have. By having to engage with such a practical and current topic and to deal with the specific questions as constructed, we had to form an answer in a way that will be apprehended by someone who does not acquire any legal knowledge, therefore showing that we have the skill of explaining complex legal concepts in a plain way, and at the same time justify our academic background by bringing a level of sophistication and legal knowledge.

The two questions posed were “if a client asks me to do a mural on the side of a building of which they are tenants, am I legally able to do this and if not then what are the consequences?” and “what rights do graffiti writers and street artists have over their images, specifically if their work is photographed and used online?”. Almost immediately, one can tell that the questions posed are clearly practical and verify the aforementioned. I personally found very important the fact that they were posed rather early, so the whole process of researching the relevant law on the matter was yet another incentive to acquire in-depth knowledge of graffiti and street arts and all the possible aspects they might entail. Sinna One’s comments that he found the answers useful was really rewarding, as it reflected our efforts to provide trustworthy responses to his queries.

Sessions

The first session, with the tour around the city, was a great opportunity to gain context in our perception of street art and graffiti, to get a first idea of the “hot spots” of Brighton and to be introduced to the various different styles that can be found out there, in the street: from simple depictions of the famous Brighton touristic attractions to street art with strong and unequivocal political messages and from graffitis that self-promote local crews to tributes of heroes of the popular culture. Accompanied by comments of some background knowledge by Sinna One, the tour was undoubtedly invaluable and a springboard for all of us to further engage with the essence of the project.

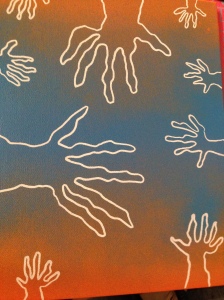

Thereinafter, the art therapy session in Art Schism with Sinna One was again an interesting and useful experience. Firstly, because it was the first occasion to meet with each other and come closer in an ideal environment: sitting side by side and commenting on our objectively amateurish creations in the paper and canvas. Secondly, and more importantly, because we experienced first-hand the impact of creating a piece of art and the feeling of achieving something that you had no idea you are capable of. Even though it is a known stereotype the saying that “art can liberate”, seeing it in practice makes you wonder the potential impact that such sessions have in pupils expelled from mainstream education, young offenders and inmates in general.

The visit on the Youth Offending Service was also enlightening, even though not directly related to our project. It was frustrating realising that the cuts of the central government, result to the decrease of induction programmes which aim at assisting young offenders, the people who need support the most. Moreover, the confession of the staff that art-related programmes were abandoned partly because of the inability to measure their impact was also a discouraging issue. Additionally, what seemed to be problematic was the conflicting approaches towards graffiti and street art (as demonstrated in the presentation by referring to the example of the confused young offender having to wash a graffiti and the next day be asked to create one as part of his induction program). It is known to us, law students and professors, that the nature of the law is conservative and that reformation on a mater can be lengthy. Therefore, it is required by pubic services, such as the YOS, to take the initiative and construct a uniform stance towards graffiti and street art: creating art pieces in designated areas should be encouraged and protected legally (i.e. rights vested in the owner). However, at the same time, one can feel nothing else but admiration for the overall work of the people there and the dedication they demonstrate.

Lastly, the double session in Brighton Youth Centre functioned ideally as a conclusion to the project. It was a reaffirmation of the facts that Sinna One, besides a talented artist also acquires the means to communicate his knowledge and that art contains some sort of therapeutic ability. It was truly remarkable seeing pupils arriving in the sessions and having an unengaged attitude toward it quickly be transformed as soon as they were asked just to draw something on a piece of paper and even approaching the session more enthusiastically when asked to paint something on the wall. And that is why street artists should be further encouraged to contribute in project as that one: given the appealing character of that form of art in young people, artists can be used as a proxy and educate them.

General Reflection

Street Law Brighton, besides the obvious outcomes (e.g. get a grasp of the law in relation to ownership of graffiti and street art in general), managed to achieve so many things: it provided us, the students that participated, a different approach in the way we see the actors of graffiti and street art in general as we got to know a person with a deep knowledge and involvement in the local scene (Sinna One); it re-introduced Brighton putting in the frame some admirable pieces of art which are scattered all around the city and it made us realise how interrelated is aesthetic with the wellbeing of people within an urban environment; it posed questions that only a legal practitioner on the relevant branch of law will have to face and it made us consider certain legal issues in a more practical manner, away from the academic approach accustomed in the law school; and it demonstrated the therapeutic aspects of street art and their impact to the local community, primarily by giving us a first-hand experience as we had the opportunity to participate in an art therapy session in Art Schism, and secondarily by giving us the opportunity to discuss relevant programs run by the Youth Offenders Service and assess their impact on children and additionally to witness a two-part workshop session in the Brighton Youth Centre.

Personally, the most enjoyable part of Street Law Brighton was the session in Art Schism, where we were introduced to the therapeutic abilities of art. It was a first time experience and it helped me correlate (apprehending the impact of creating art on them) with the young pupils during the BYC sessions. I also found interesting the BYC sessions, because even though it did not go as planned, by mixing the teams, it gave the opportunity to all members of the SLaw team to come closer and further familiarise with each other. At the same time, this series of sessions was the most troubling as our engagement with the pupils was low. Without degrading the work done from all of us and especially from our tutor, I believe that a redesign of this session is necessary so that enhancement can be achieved: e.g. forming teams (pupil/law student) and engage in tasks that require cooperation theoretically will provide the necessary intimacy to both the pupil and the student and the latter will feel more free to ask things relevant to our project (legality/illegality; how ownership is perceived; etc.).

As far as the current stance of the law, it might seem logical that the legislative framework regarding graffiti and street arts is vague at the moment, keeping in mind that it is a newly-introduced phenomenon in its current form, highlighting the artistic aspect and less the action of vandalism and incitement of criminal behaviour per se, however as it becomes more and more appealing to young people and consequently more commercialised, an unequivocal and unambiguous piece of legislation is deemed necessary.